Projects

This page contains a number of projects I have previously or am currently working on.

astro

This project is a significant rewrite of a space shooter game I first programmed at the age of ten, in fifth grade. The original version was filled with what kind of code a ten year old programmer would write in cobbled into 4,000 lines of Python. When I was in my freshman year of high school I decided to rewrite it from scratch because I could not stand the original codebase.

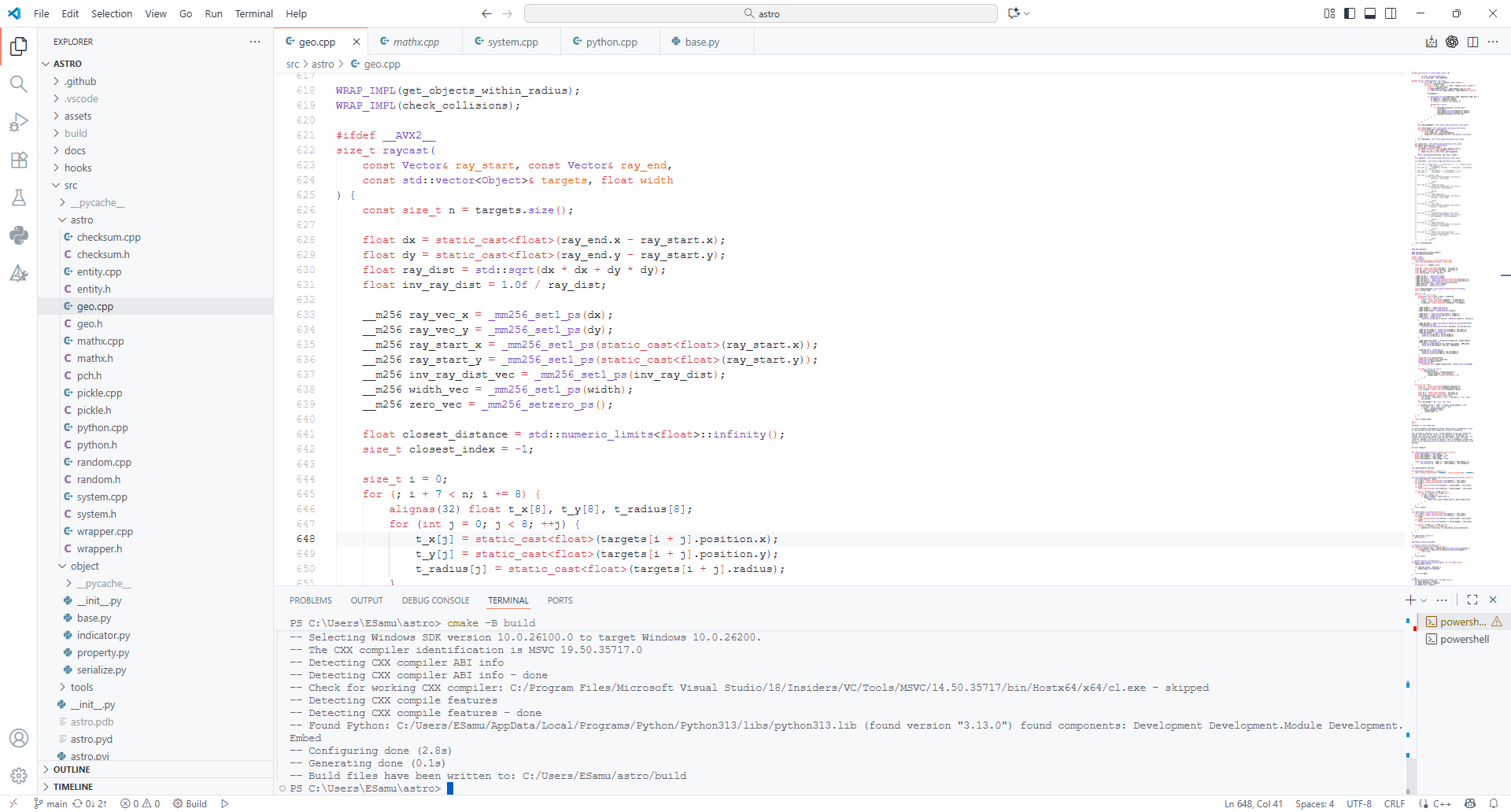

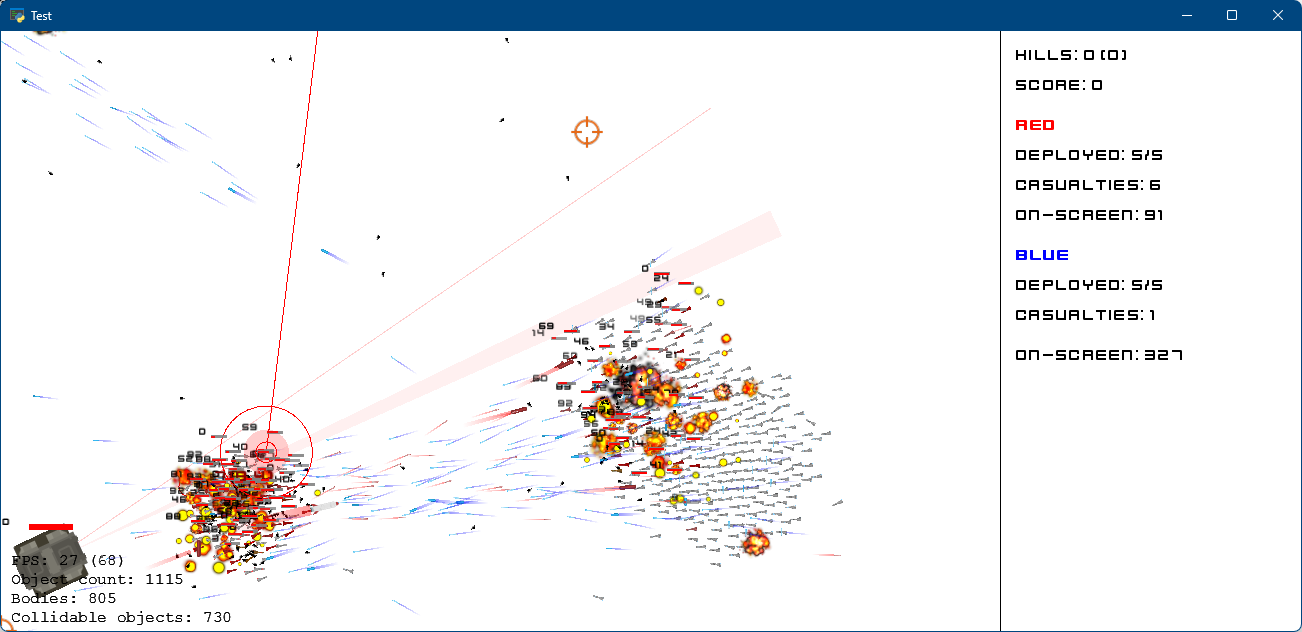

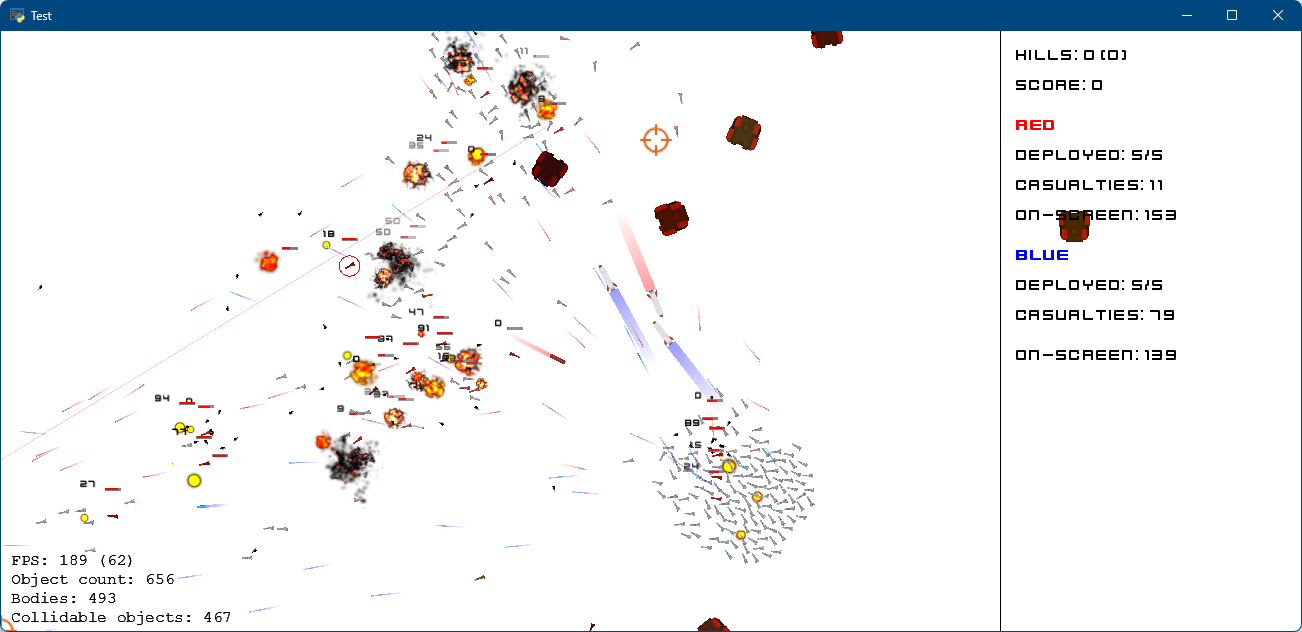

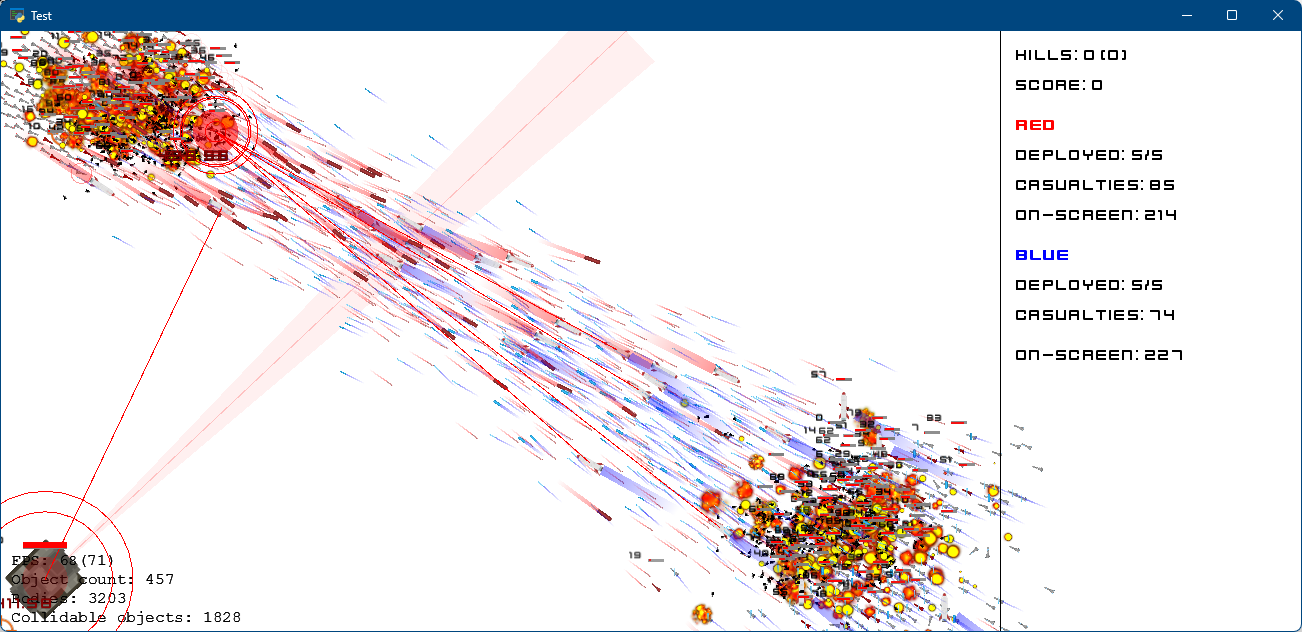

The new version is built using Python and C++. Python is used as the front-end, such as object behaviors and general game logic. C++ is used for performance-critical components because of the number of on-screen objects, including physics, collision detection, raycasting, pathfinding, and various trigonometric/mathematical functions.

C++ and Python are connected through a custom highly optimized C++ wrapper around the bare-bones internal PyCore implementation of the Python C API. This wrapper removes all forms of error checking and optimizes it to prioritize maximum runtime performance over safety.

The project is on GitHub under eschan145/astro but it is unfortunately not open source, although I do have intention of making it so in the future. It is comprised of approximately 66% Python code, 31% C++, and the remainder GLSL and other scripts.

Features:

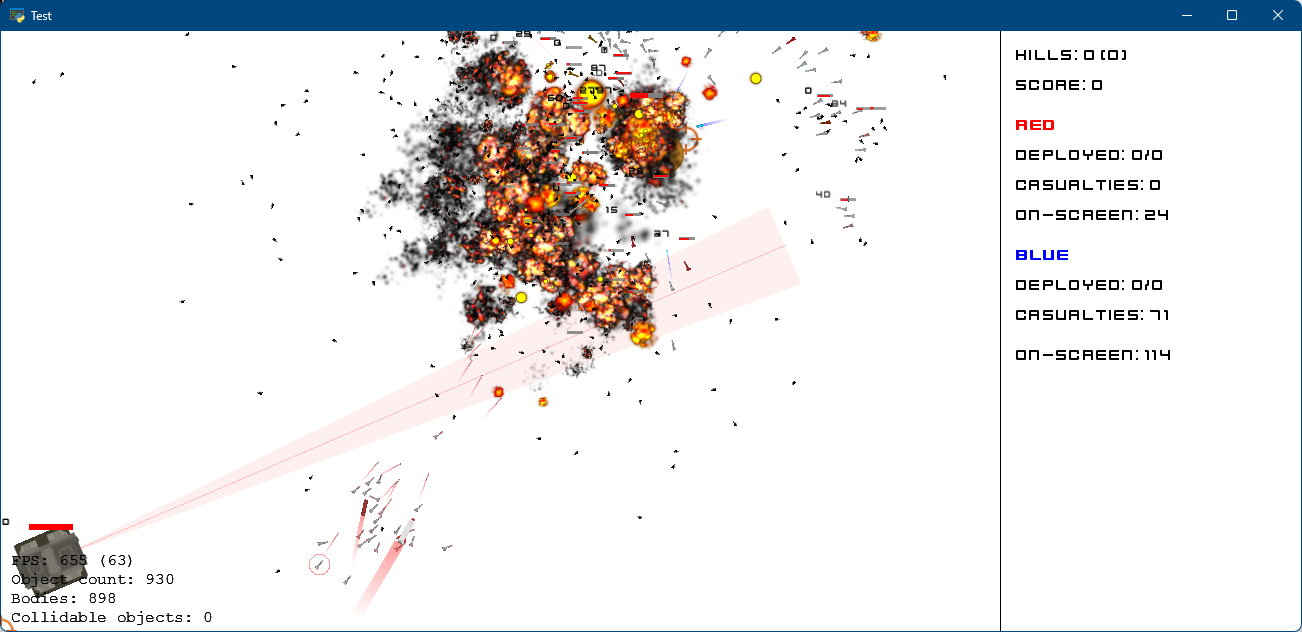

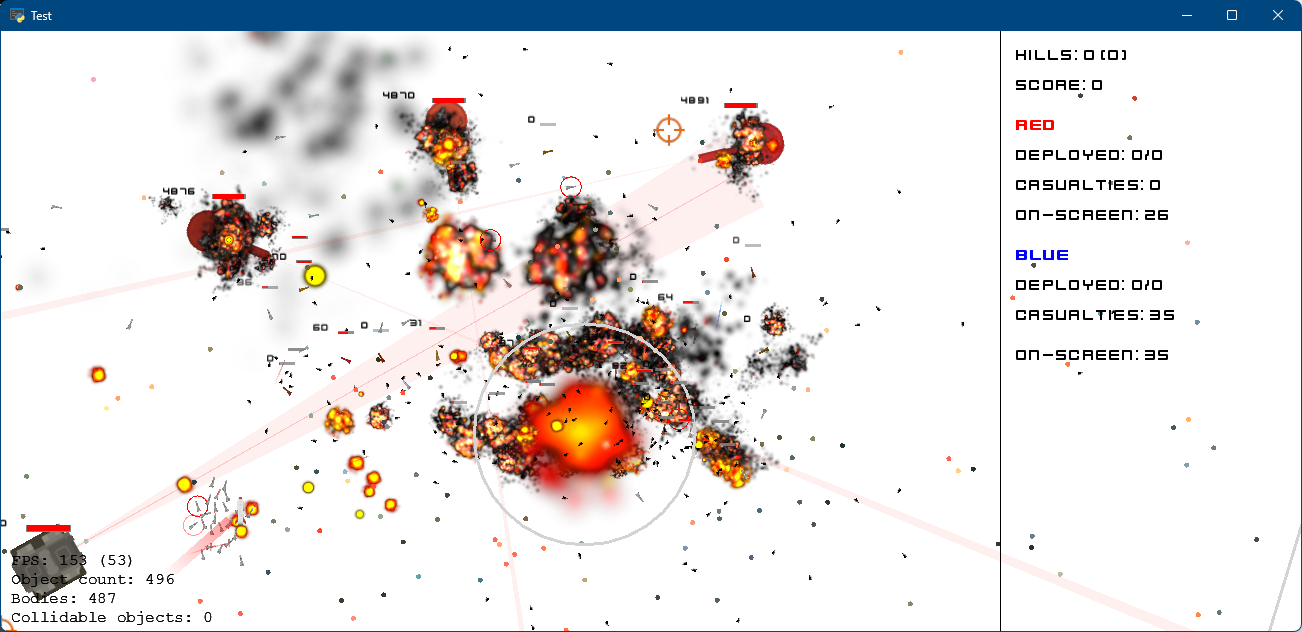

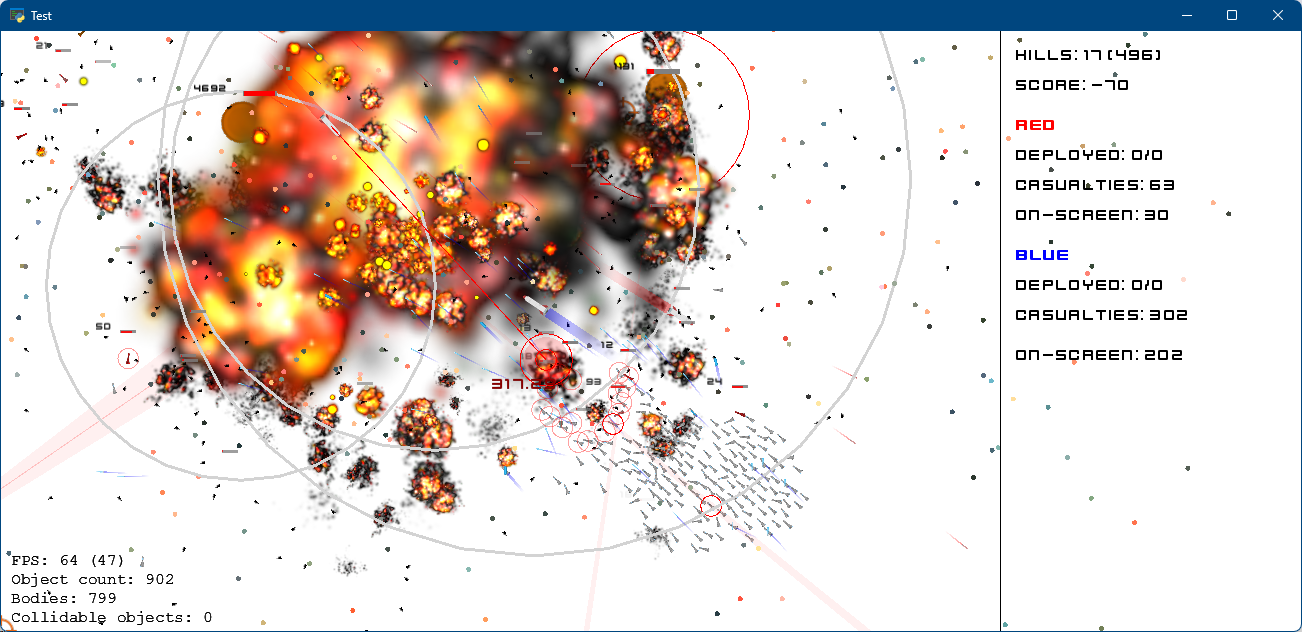

- Continuous collision detection with OOBBs. Broadphase is parallelized through the GPU with OpenCL, narrowphase is parallelized for multicore CPUs with OpenMP.

- GPU-accelerated shaders and particles.

- Advanced Vector Extensions (SIMD AVX2) optimized smart projectile targeting and raycasting.

- Fully-featured world/map editor.

- Serialization/deserialization of worlds with checksums and binary file storage.

- High-performance physics, including explosion physics.

- Very easily extensible to add new objects and entity types with completely modular object and property system.

Gallery

Click on an image to view its description

C++ with Python API vs cPython benchmarks: 0

Each iteration is a for loop and a function call. They are made to be equal; calling one versus the other is calling a different function. The same parameters are used, and setup such as initializing objects happens before the timer starts. Batch processing is not utilized; for example the distance benchmark calculates the distance between two points 200,000 times with 200,000 individual function calls. In this case, the overhead of marshalling data back and forth per function call is higher than the actual computation. Based on testing I have done, I am very certain that the benchmarks below exhibit lower FFI overhead than most C++-to-Python frameworks such as SWIG or nanobind, though I haven't tested them thoroughly enough to make a definitively strong argument. However unlike these frameworks that wrap C++ to Python almost seamlessly there is still a need to parse arguments and such manually.

| Test | C++ | Python | Speedup | Iterations | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AABB | 24.5ms | 29.8ms | 1.22x | 200k | AABB between pairs of random hitboxes |

| distance | 14.2ms | 31.9ms | 2.24x | 200k | Euclidean 2D distance |

| raycasting | 34.7ms | 503.7ms | 14.52x | 10 | Raycasting for 100k objects |

| OOBB CCD | 12.9ms | 449.8ms | 34.86x | 1 |

CCD of AABBs with velocity and angle for 10k objects

1 4 collision substeps |

| uniform | 15.2ms | 26.4ms | 1.74x | 200k | Mersenne Twister uniform pseudorandom number generation |

-

0

Benchmarks were conducted on an Intel® Core™ i7 11370H (3.3 GHz)

with 32 GB of LPDDR4X RAM. This CPU has weak multithreading with only 4

cores/8 threads, which is suboptimal for the C++ OOBB benchmark. Code was

compiled with

/Oxusing theReleaseconfiguration in MSVC 19.50, with AVX2 intrinsics (/arch:AVX2) and OpenMP (/openmp) enabled. - 1 Objects were randomly distributed in 10000x10000 space moving at 50 pixels/frame. Their width was randomized from 5 to 15 pixels, and their angle was randomized from 0 to 360. This configuration is meant to best replicate typical in-game circumstances.

The wrapper manifests in the form of a Python module that is as seamlessly called as if it was written in Python; it is completely invisible that there is a C++ extension behind. The module handles object properties, conversions, calling object functions, and such.

The custom API also makes good use of modern C++ such as implicit conversions and operator overloads. For example (implementation incomplete for demonstration purposes):

The code above can be called as follows.

The only requirement in this case is that the attribute must be in

__slots__ so the API can access it extremely quickly. Likewise, the

API does not provide any sort of error or safety checking when in Release mode;

only in Debug mode it provides a comprehensive set of error checking. If a

function is called improperly in Release (NDEBUG) mode, the

behavior is undefined and it will fail unpredictably. Examples include passing

the wrong type of argument, missing a parameter, or passing some invalid

variable. In practice, however, this has not been an issue because most

development happens with Debug mode anyways.

The below example shows what happens when an error occurs in Release mode. The

function astro.uniform() is the equivalent of

random.uniform(), but much faster and without error checking. It

shows what happens when you put a str, list, or a

module instead of an numeric type which would raise a

TypeError in regular Python. If one were to forget an argument, the

entire program crashes. Note that all of this would be quickly caught with

assertions in Debug mode.

Note the corrupted stack trace (project_swept was never called!)

This brings me to the most difficult part of implementing this wrapper

API—reference counting. PyObject* maintains a reference count

in order for Python to know whether to deallocate it or not. We can increase or

decrease the reference count with macros such as Py_INCREF.

However, there are functions that return a reference versus those that do not.

If reference counting is messed up and an object is deallocated when when it

shouldn't be, because Python thinks it isn't needed anymore, the entire program

can go haywire. There will be random use-after-frees, unintelligible stack

traces, data execution preventions, and even AttributeError at

random places, that are the type of bugs that make people quit C++ programming

altogether.

Lastly, Python does not provide error checking in all scenarios. It is strangely

possible to

return a C/C++ nullptr

(not Python None) into the Python interpreter from a C/C++

function. When printed, it displays as <NULL>, not

None. Doing anything with it will immediately cause a null pointer

dereference.